“Photography has been revealed […] in its most original, basic form: as a document and record of time. Each individual photograph retains some fraction of time, together they create an orderly record of its elapse.”

Lech Lechowicz

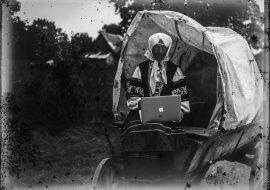

We usually think of time in the simple categories of past, present and future. This is true in photography as well—once the camera’s lens captures a scene, the moment becomes a part of what already passed, a part of history. However, one could say that a photograph that was just taken refers to the present and the future. A picture from a far-off country may stir its beholder’s imagination and bring out a desire for travel—a desire for what lies ahead. The photographic process is ingrained in the future as well. As photosensitive material is exposed to light, it creates an invisible latent image, which is going to undergo processing to reveal its contents later. Take the time to recall Alexander Gardner’s famous portrait of Lewis Payne, on death row for his involvement in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. He is alive while the picture is being taken, yet his heartbeat will cease in a moment. To quote St. Augustine: “If nothing passed away, there would be no past time; and if nothing were still coming, there would be no future time; and if there were nothing at all, there would be no present time.” In other words, the present moment is realized by that which was and that which will be, and a portrayal of “death” (after all, time is embalmed in photography) brings a reflection on the inevitable.

Contrary to the Platonic theory of ideas, “in photography, the presence of the thing […] is never metaphoric,” says Roland Barthes, and each thing depicted is considered the “private appearance of its referent.” It’s an impartial witness, a footprint, a slice of reality. Thusly we can take part in past events. We interact with the past not only in the cognitive-anthropological sense, but we also come face to face with what really was. Although mysterious and inaccessible, a photograph assures us of its subject’s existence. This certainty comes from an interpretation of “what-has-been.” It testifies to a presence within time. Although it restrains recollection, it is memorial of past moments. It makes the past as real as the present. And although the present “slips through our fingers,” in photography we can “take hold of the past.”

This year’s International Photography Festival Białystok Interphoto features artists whose works, in many different aspects, relate to the heterogenous concepts of Time. Artists who work with the photographic medium in the context of linear flow and capture. Others, who reflect on the Barthesian punctum, or who symbolically evoke sociohistorical elements in their image, as well as the artists whose vision and innovative frame influenced the contemporary forms of expression employed by successive generations.

Historical exhibitions, for example, Polish and Czech avant-garde or subjective photography in Polish art, will expose the continuum of changes not only in the medium, but also in modern understanding and reception of art.

Presenting the public with postmodernist criticism on appropriation and record will uncover contemporary photography as a tool for control. From almost the very beginning of the modern age we are strongly linked to the past, not necessarily ours. An immobile picture captures time and becomes like an incorruptible memory. This trustworthiness brings out feelings of unwavering endurance and stability. Photography does not recollect the past, but ascertains it. What is seen in the picture truly did exist. A photograph is indisputable. History that is recorded on celluloid or digitally is true. It serves as proof for historians, architects, sociologists, and all researchers of the past as well as private, personal, individual stories. Although, what is a “true” narrative.

Human memories are temporary and individual. They slowly disperse and decay. They are obstructed by other events. They vanish with every cell, all of which are designed to end. During the Interphoto Festival we will consider if the testimony of photography isn’t far superior to this. If it can be reproduced and become durable. If the camera should become humanity’s instrument in creating infallible and true memory that future generations could refer to.

“The true picture of the past flits by. The past can be seized only as an image that flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again.”

Walter Benjamin

Grzegorz Jarmocewicz

Artistic Director of the festival